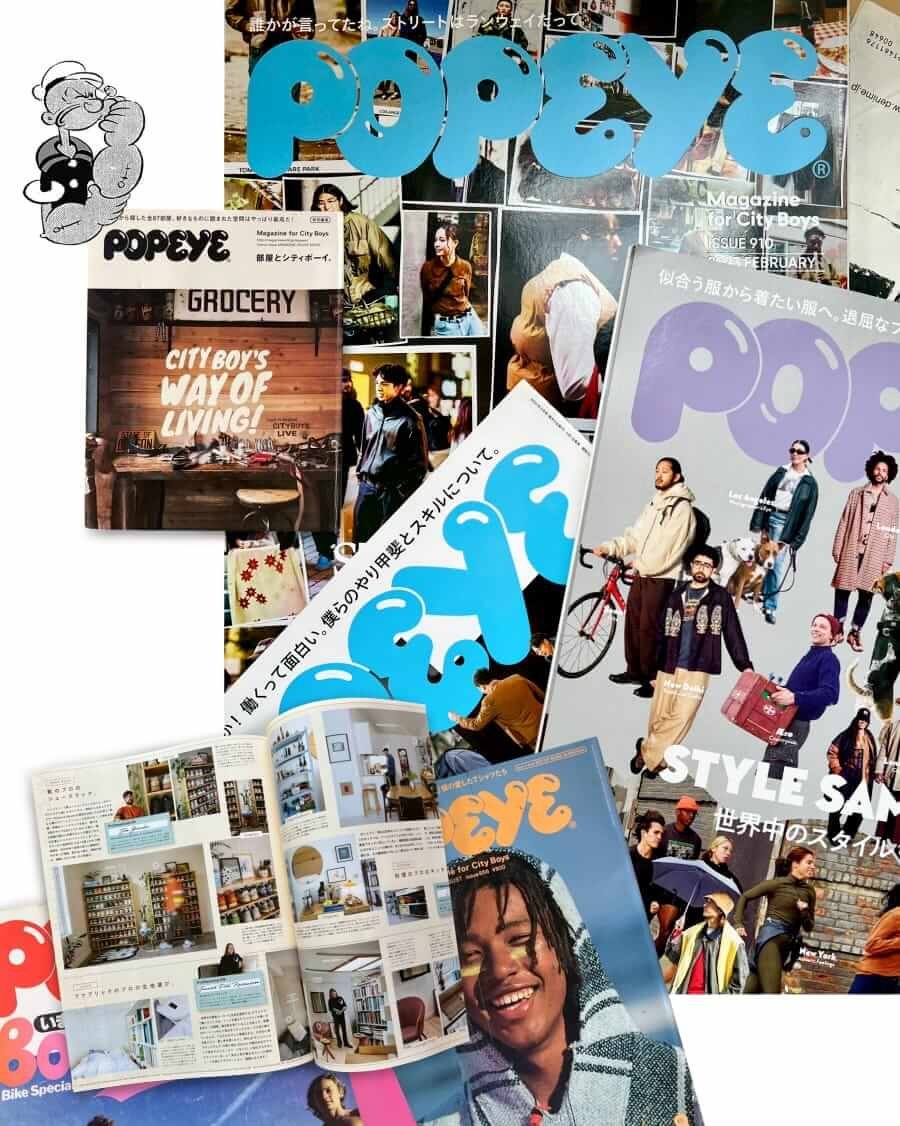

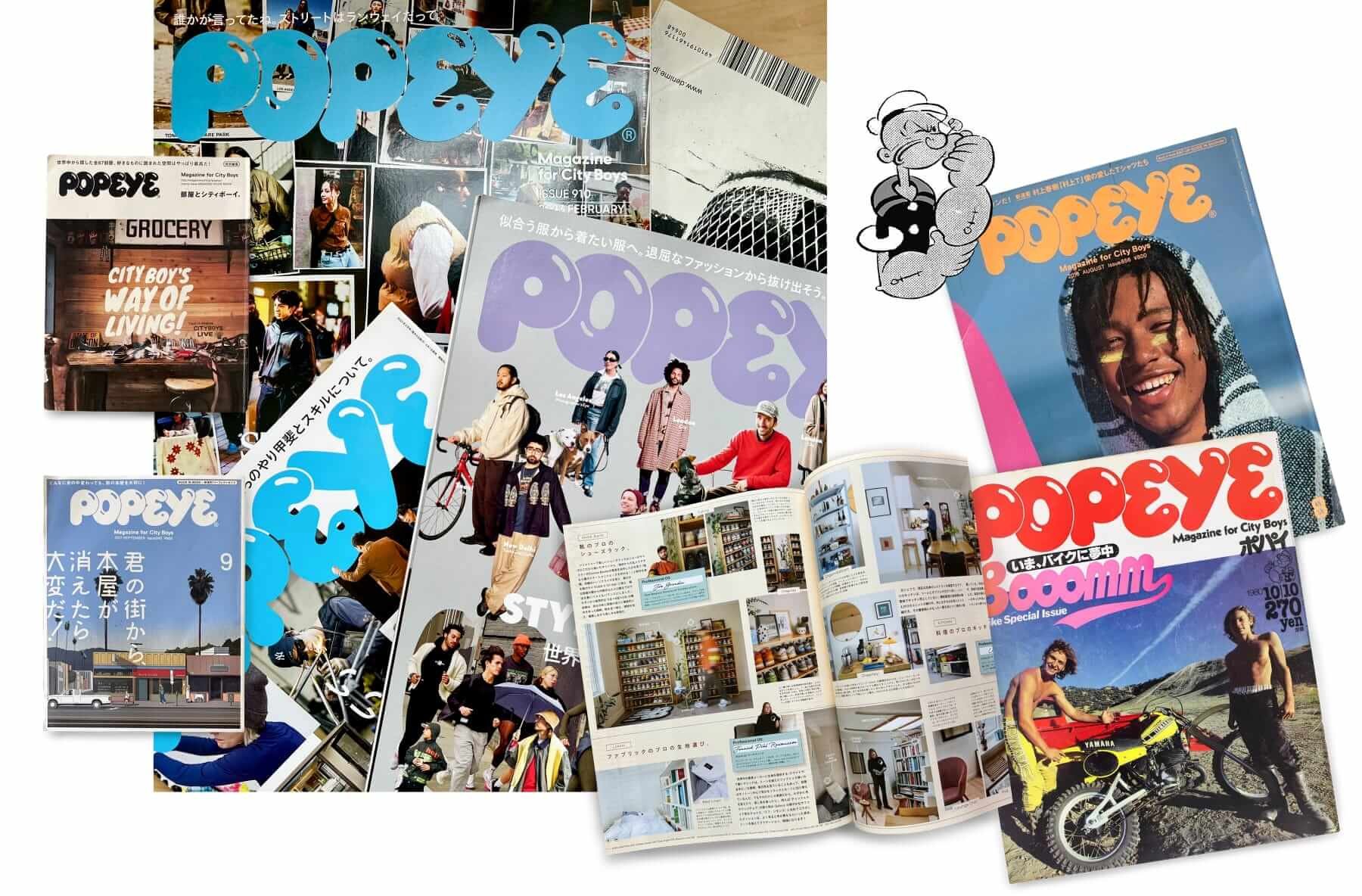

After 48 years in print, the Japanese lifestyle magazine Popeye remains a vital part of the country's consumer culture. Its unique coverage of fashion, music, interior goods, food and travel make it a monthly bible to the latest in Tokyo style, and increasingly, a vehicle for spreading Japanese tastes around the world.

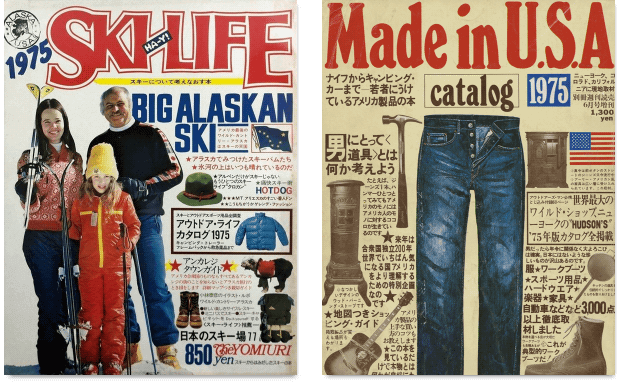

The magazine debuted in the summer of 1976, the brainchild of an older editorial executive Yoshihisa Kinameri and his younger protege Jirō Ishikawa. They had been rogue editors at Heibon Publishing (currently, Magazine House), and while in exile at a poker card-manufacturing subsidiary, they edited two hit publications for other companies: a magazine about American ski culture called Ski Life and then a bible of American consumer goods called Made in U.S.A. The overwhelming success of these among young people encouraged Heibon to call Kinameri and Ishikawa back to the main office with the tantalizing offer of making their own magazine. They decided to base the magazine for young men focused on the athletic lifestyle of West Coast teens. Their first step was to get on a plane for Los Angeles to do research.

The Series

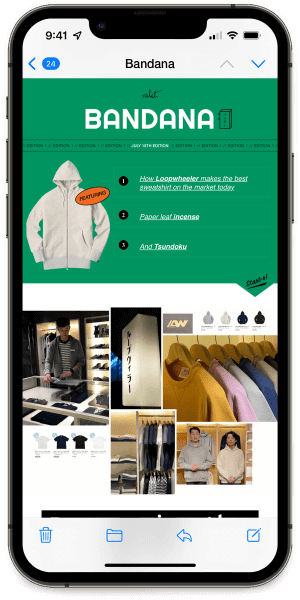

For Bandana, our Japanese-focused newsletter, we're starting a new series that will highlight Japan's diverse magazine culture. First up, W. David Marx, author of Ametora and Status and Culture, shares the origin story of Popeye magazine and what has made it such a beacon of Japanese style for nearly half a century.

Advertisement

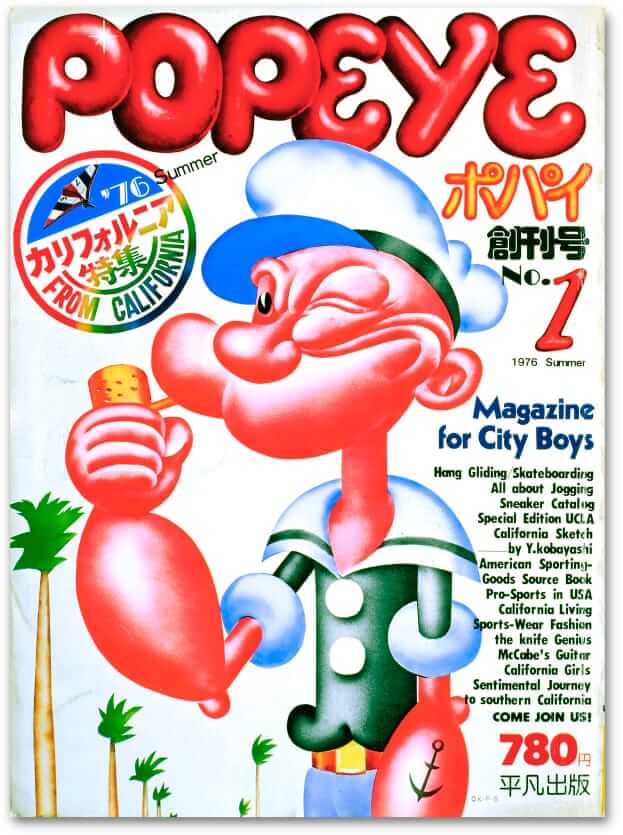

Ishikawa wanted to call the magazine “City Boys”—a popular buzzword at the time meaning sophisticated urban youth. But Kinameri saw the cartoon character Popeye's name written out in English and realized that it split into “pop eye”. This would make the perfect magazine name—keeping an “eye” on “pop”. In getting permission to use the name from King Features Syndicate, they also could use the Popeye iconography (which is why the later big brother title was Brutus and the sister title was Olive.) The first issue of Popeye: Magazine for City Boys debuted in June 1976 with a focus on California sports such as skateboarding, surfing and hang-gliding. In 2016, as celebration of the magazine's 40th anniversary, Popeye reprinted its entire first issue as a bonus feature.

The magazine was a quick success, and it stoked renewed interest among Japanese teens in American pop culture. The effect was so immediate that rumors swirled around that the CIA secretly funded it as a psy-op. But from the beginning, the magazine focused on emerging American youth subcultures and became a go-to source for teens who wanted to know the latest going on overseas. In the very first issue, Popeye covered Jeff Ho's Zephyr surf shop, which sponsored the legendary Z-boys of skateboarding history fame.

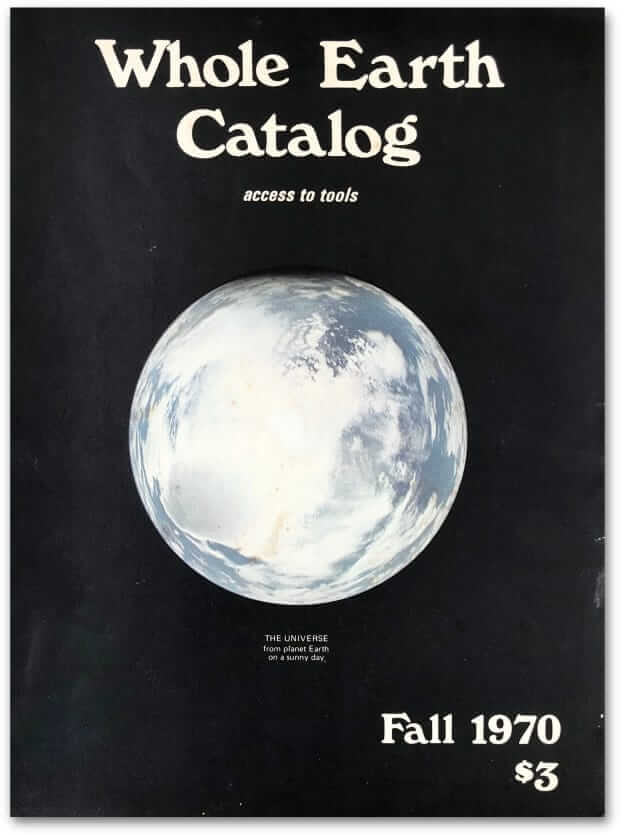

But Popeye's greatest innovation, in inspiration from the Whole Earth Catalog and L.L.Bean catalogs, was a layout that showed hundreds of cool products, with prices and retailers, so young men could shop before they shop. Readers loved it, and it was a format that could easily be adapted to the zeitgeist: from UCLA campus gear in the mid-1970s and preppy fits later in the decade, to European and Japanese designers in the 1980s, and street fashion in the 1990s. Popeye always changed with the times, but the focus on consumerism remained.

Advertisement

With the growing respect for Japanese menswear in the late aughts, Popeye no longer just wanted to introduce readers to the latest global culture. Instead it became an important media resource for creating and celebrating the unique cosmopolitan culture emerging in Tokyo. Under the editorial guidance of frequent The Sartorialist subject Takahiro Kinoshita, Popeye experienced a renaissance in the mid-2010s, with a distinct new aesthetic that put trad-chic fashion set against the city's iconic mid-century establishments. And by reporting on similar lifestyles around the globe, it seemed like there were truly “city boys” in London, Paris and New York as well. By the late 2010s, Popeye stylist Akio Hasegawa pioneered the “big silhouette” look of loose sweat suits and sportswear that presaged the current wide fits of J.Crew. Kinoshita later left to run Lifewear magazine at UNIQLO among other projects, and Hasegawa currently runs his own brand Cahlumn using Popeye alumni to make its impressive catalog/magazine.

Even today Popeye continues to push a unique Tokyo aesthetic, and the audience has expanded out from young men to older guys, women, and foreign readers (who often can't even read the texts). Despite the advertisements from major global luxury brands, Popeye has its own sense of how to style such products into a laid-back look using teenage models. There are kids with great style sense walking over to the flower shop in chic gray sweatsuits or enjoying antique ceramics in their tatami rooms while wearing high-end tanktop undershirts. Compared to foreign fashion magazines, Popeye celebrates craftsmanship and urban exploration, especially among older eateries and generation-old shops rather than the latest trendy restaurants.

Popeye, especially as a print magazine, maintains a focus on concrete, analog things—real objects, real places, real people. And this may help ground the magazine in a time of Instagram and TikTok. Even with its social media accounts, Popeye offers an aspirational perspective on living in Tokyo and discovering the wonders hidden around a street corner or finding a great jacket from a small clothing brand. To this day Popeye remains a “magazine for city boys”, and now those city boys are everywhere.